In May this year I had the privilege of attending the 72nd CFA Institute Annual conference in London. The CFA institute is a global association of investment professionals with the Chartered Financial Analyst designation. I was particularly interested in the theme of the conference, Disruption. Not only is the world facing an economic slow-down, but we are also caught in a convergence of disruption – greater even than that of the Industrial Revolution. It is the intersection of climate change, alternative intelligence, the explosion of data, tectonic geo-political shifts and demographic change. All factors that simultaneously create uncertainty and opportunity – and within each lie a myriad of potential pitfalls. All of which affect our daily lives.

I recall my impressions and some related thoughts in this article.

Geo-political alignment

Geopolitical strategist, Peter Ziehan, explains that the stability following World War II was maintained through a trade-off between the US and its allies. The US ceded economic benefits to other countries in exchange for their participation in a global defence network. Now however, foreign relations are driven by self-interest and the old global order no longer serves the US interests – which economically, Zeihan says, it was never supposed to. Zeihan points out that the current landscape, where countries have spent decades building interconnected economies featuring global trade networks, is coming to an end. This is being played out notably in the US and UK.

Historically, the US has spent decades building a military force with no emphasis on trade. Now however, the Trump administration is no longer giving away military protection for free. For the first time the US is looking after its own interests, looking inward, and already this has had a dampening impact on global growth. In addition, there is no clear strategy to this new vision, which is disruptive in itself. Trump’s pronouncements are made in a haphazard fashion, sometimes in early morning tweets, and often contradict earlier strategy. On the other side of the ocean, the United Kingdom is preparing for a hard exit from the European Union. Zeihan maintains that: ‘This combination of factors is bad news for the United Kingdom. There is no version of Brexit that will lead anywhere other than a hard divorce.’ He expects that the United Kingdom will ultimately lose its ability to negotiate from a position of strength with anyone outside of Europe. He also asserts that the United Kingdom will lose its status as a global financial hub and that it is likely that half of those deals will go to the United States.

In the months to come, we can expect a continued unravelling of the global order, with the United States becoming the biggest disrupter.

You can watch the full video here.

Climate change

Whilst in London, I read an article on how the impact of climate change could potentially signal human extinction. It really grabbed my attention!

Climate change will disrupt humanity on every level and in every sphere. It will cause increasingly volatile weather patterns – with an increase in droughts, fires, floods, earthquakes or tsunamis – all of which will impact anything from food production to insurance premiums.

For example, should temperatures rise to levels predicted by researchers (now an accepted ‘fact’ per the Paris Accord), the production of corn in the US could fall by as much as 20%. Bearing in mind that the US is the world’s top food exporter and that world demand for food is expected to increase by 60% by 2050, the impact of climate change is significant.

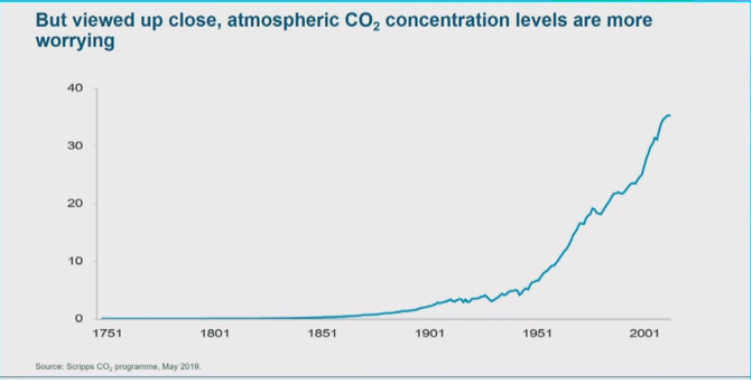

Whilst not the only factor, the primary cause of climate change is the rising level of carbon dioxide. This has an effect, amongst other things, on crop nutrients and human health according to the International Food Policy Research Institute.

My teenage daughters highlighted climate change for me when they started changing their consumption habits, specifically of plastics and harmful materials. My eldest has cut plastic from her life, including her beauty routine! My youngest stood in the kitchen at breakfast and announced that she was no longer eating Nutella because of the harmful impact that palm oil farming has on the environment.

They are part of the Gen Z generation – the first generation of true digital natives. Mckinsey’s 2018 study on Gen Z, identified their four core behaviours which are all anchored in one element – the search for truth. In other words, they are cause-driven and they will be the generation that pick up the pieces after earlier generations have mindlessly consumed their way through the environment.

It is only when our consumption patterns change, i.e. that we stop our insensible consumption, that we may see a positive impact on global growth. But the patterns of consumption need to go beyond the individual.

The conference panels highlighted the need for increased intervention by both governments and the investment community. Investment policies need to promote environmentally friendly investments and simultaneously invest in new technologies and companies battling climate change.

Unfortunately, governments have been slow to act: some still deny climate change and some are too busy with geo-political battles to focus on what the Global Risk Report pegs as the ‘greatest risk to our world’

The response of young people, to both the squandering of natural resources and government’s lack of response to the crises, is increasing anger. This in turn will force political change as they become involved in politics as an agent of change. Which is in itself yet another disruptive factor.

Capitalism under threat

Anne Richards, CEO of Fidelity International, examined three main factors threatening the capitalist system:

- The unequal distribution of income

- Demographic changes and again,

- Climate change.

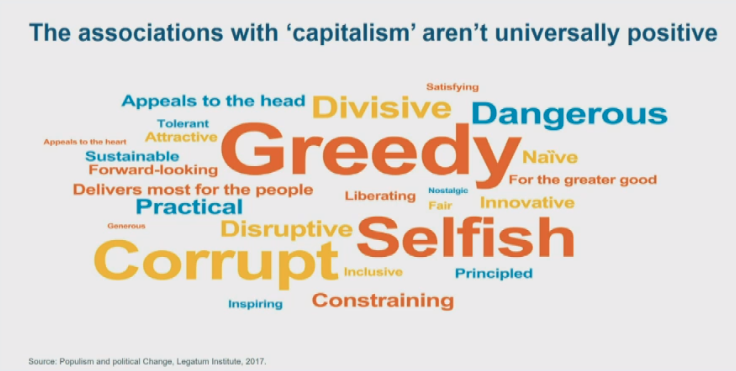

Young people have suffered the most from the credit crises fallout. They are disillusioned with the system. The association with capitalism across the board is no longer positive.

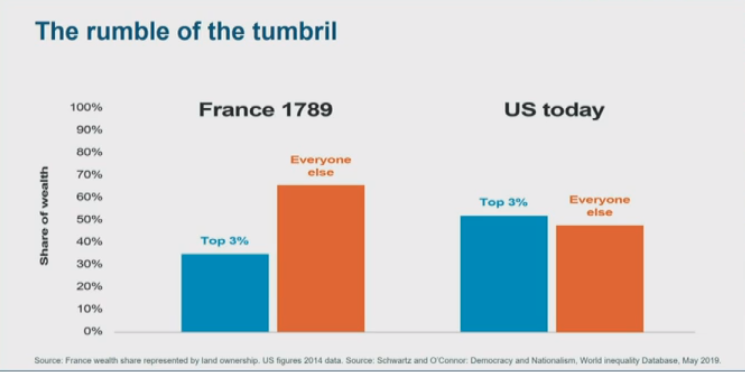

Wealth is now more unequally distributed in the US than before the French Revolution, which led to the literal rolling of heads. The top 3% of wealth owners now have as much wealth accumulated as everyone else in the system combined.

When there is an impression that the system which created this unfair distribution is itself unfair, the public will increasingly turn against the system. This is already evident in the rise of nationalism and populism around the world.

On climate change, Richards pointed out that the window of opportunity for the finance sector to direct flow towards climate-friendly investments, on their own terms, is closing. The finance sector has not done enough to stem the impact of climate change. The finance sector runs the risk that changes will be made for the finance sector, in the form of legislation, which may not necessarily be in the interest of the ultimate asset owners like pension fund members.

Ultimately, if people think that the future of the system is not in their favour, they will abandon it. Joseph Chamberlain, a British politician and social reformer in the late 1800’s, said: ‘What ransom will property pay for the security it enjoys?’ This means that the wealthy will increasingly pay for the security of their position. This ‘payment’ can take the form of punitive taxes and increasing legislation to direct the wealth towards the poor, or a changing of the guard in global leadership.

Demographics

I took away three demographic trends which are already causing disruption:

Globally the world is ageing due to longevity and the decline in the birth rate of most countries. It means that there are not enough productive, young people to sustain the systems built when population growth was taken as a given – such as social security or pension systems.

Regions with low population growth or declining populations need young and productive people to boost their workforce – and most of these people will come from poor regions such as Africa or war-torn places like Syria.

In addition, the existence of better economic opportunities and the perceived safety of certain countries will continue to convince immigrants to reach countries like the US and the UK. The immigration problems of these nations are unlikely to go away soon.

Population growth typically still exists in emerging economies with most growth in poor countries, i.e. Africa, India and South America. Population growth, if converted into production growth has every potential to provide economic growth, opportunities in these countries.

The rise of big data causes dilemmas for ethics and governments

Data is the new currency, according to Professor Viktor Mayer-Schonberger. It is the owners of data who have the power and who have benefitted from an ever-increasing share of the profit – above that of capital owners or labour. It’s the likes of Facebook, Google and Amazon who have obtained an early advantage by collecting data.

The concentration of the world’s data in the hands of a few companies and in the absence of regulation poses enormous ethical issues – as seen in Netflix’s searing documentary The Great Hack. The influence of data manipulation in elections and the barriers to competition with smaller companies have already become a major concern. Traditional policy measures such as competition regulation appear outdated to deal with these challenges.

The rise of artificial intelligence poses problems

Artificial intelligence poses threats for any job defined by the routine application of human intelligence. Just as automated machinery and robots replaced routine manual jobs, artificial intelligence will now replace higher-order intelligence jobs such as evaluations or diagnoses. This threatens jobs, for example, in the medical and accounting profession.

Governments and society have not responded to the potential threats of millions of higher-order job losses in any meaningful way.

Conclusion:

Most of these disruptive forces challenge conventional wisdom and existing government policies. They have already challenged our understanding of cause-and-effect in economics and politics. We can no longer rely on experience for future guidance as we did in the past. These forces bring extraordinary uncertainty to our daily lives and pose real threats to our wealth and even existence.

However, the biggest mistake we can make is to anticipate no response from humans, society or governments. It is worth remembering that humans have had to make remarkable recoveries in the past, and challenging times have often led to great innovation and growth. WWII for example, was a time when innovation in communication and technology sped up and became the drivers of further innovation after the war. University London College professor Mariana Mazzucato, who also happens to be the founder/director of the Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose (IIPP), observed that past great innovations, such as smart phones or green energy technology, were developed off the back of large-scale government-led research. She maintains that collaboration between the public and private sector is key for determining the success of our future.

We highlight our recommendations on appropriate responses to these disruptive forces in separate articles: “How do we protect our wellbeing in disruption?” and “How do we react to disruption with our money?“.

In closing, I summarise what our response should be, based on the advice given by Mohammed A. El-Erian, chief economic advisor of Allianz:

- Cultivate intellectual curiosity and open mindedness.

- Understand that some basic structural relationships have changed.

- Explore behavioural biases at a time when behavioural traps have increased: be it the challenges of blind spots, unconscious biases, asymmetrical framing, and active inertia.

- Most of all, have a relentless focus on resilience, agility and optionality.